Search for a Site

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page GGMG 1880 – 1961

A medical practitioner who served briefly in World War I with the Australian General Hospital in Egypt and 3 Casualty Clearing Station in France, he was elected to parliament in 1919, becoming Country Party leader in 1921, and Deputy Prime Minister in 1922. On the death of prime minister Lyons in 1939, he briefly became caretaker, and subsequently Minister for Commerce.

Page’s last major role was as Minister for Health (1949–1956) in the post-war Menzies Government. He retired from cabinet at the age of 76, and died a short time after losing his seat at the 1961 election. Page served in parliament for almost 42 years, and only Menzies lasted longer as the leader of a major Australian political party.

In the 1949 Menzies government, as the Minister for Health was in the negotiation chain for the Portsea site for OCS.

He retired from cabinet at the age of 76, and died a short time after losing his seat at the 1961 election.

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies KT AK FRS QC 1894 – 1978

Bob Menzies studied law at Melbourne University and became a lieutenant in University Regiment. He went on to become a prominent lawyer, however his resignation of commission in 1914 later drew the quip from political rival Arthur Caldwell ‘A brilliant military career cut short by the outbreak of World War 1’.

He entered the Victorian parliament in 1928, becoming deputy premier in 1932. Shifting to federal parliament two years later, he was appointed Attorney General and later Privy Councillor, and in April 1939, Prime Minister until 1941.

He made a comeback with formation of the Liberal Party in 1945, gaining government from a tired Labor administration in 1949, after which he remained Prime Minister until his retirement in 1966.

A strong Defence supporter from his wartime experience, he was also ‘British to his bootstraps’, with Australia being involved in Korea, Malaya-Malaysia and Vietnam during his watch. The planning to support the UK in any conflict in the Middle East and introduction of National Service in the 1950s led the demand for officers which led to the establishment of OCS.

The Directorate of Military Training’s initial site for the proposed Officer Candidate School at Lonsdale Bight was speculative rather than as a result of a proper assessment. The facilities there were both limited and primitive, so after a review of existing properties throughout Australia by the Director of Quartering which produced nothing with suitable size and facilities, attention quickly shifted to the eastern side of the Heads, where Fort Franklin had a range of accommodation and training facilities somewhat more adaptable to the needs of the courses to be conducted. This facility had been leased to the Portsea Camp Committee in 1948 as accommodation for the Lord Mayor of Melbourne’s Youth Camps so cancellation action was commenced, effective May 1951, but political opposition was quickly rallied to prevent this resumption. Army Minister Jos Francis was lobbied by a deputation of the Lord Mayor and his Committee sufficiently effectively for him to discuss the situation with Prime Minister Menzies and direct that this takeover was to be avoided ‘if at all possible’. The deputation had been able to divert his attention elsewhere as he then conferred with Health Minister Sir Earle Page who agreed on 4 July 1951 that the Portsea Quarantine Station could be made available for a number of years for the Officer Cadet School. An immediate Army Headquarters reconnaissance was enthusiastic about the facilities thought to be on offer, the Quartermaster General also concluding that the cost of works required would be a third of that required for Franklin Barracks (1).

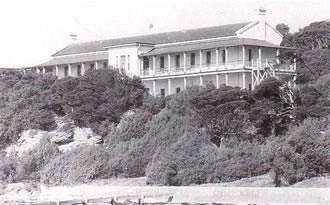

A Magnificent Site

Portsea Quarantine Station looking west to Point Nepean; while there was strong resistance to Army’s use of the area and other sites were proposed, the true believers knew that it was just the prestigious locale for an institution with the status of the Officer Cadet School. They persisted and won a campus equal to any.

RMC Archives

This windfall was not, however, as easy a picking as Francis had thought. Although Department of Health planning for major quarantine centres had been revamped to make Fremantle and Sydney the preferred sites, and Page had agreed under that apprehension, his Health bureaucracy was just as obsessed with retaining property as was Defence. On intervention from his Secretary, Page watered down his initially broad acquiescence to temporary use of limited parts of the Station for six months, on condition that it be vacated within 12 hours in the event of any quarantine requirement, and that Army undertake to vacate the premises as soon as alternative accommodation could be made available: the six months was eventually extended to 12, and the 12 hours extended to 24, but this limitation sparked Army action to find alternative sites for a permanent location (2).

Map 1 – Western Mornington Peninsula

A second survey was therefore carried out by Eastern, Southern and Central Commands, Rottnest Island having been eliminated due to its isolation and a somewhat cryptic General Staff requirement to have the School ‘within easy reach of DMT and other AHQ officers’, a situation on which the prospective commandant would no doubt have had differing views. Craigieburn guest house at Bowral and Franklin Barracks were the only two existing establishments listed as available: with the former considered expensive and not able to be expanded, and the latter not to be taken back by ministerial fiat, the remaining alternative was to build a school from scratch. This was rather inconsistent as the £110,000 purchase price for Craigieburn plus range construction would obviously be less than that of building a whole new complex, and the cited tightness of works funds would apply to a bare site as much as to any other, particularly as the preferred site was identified at Seymour, a bleak prospect compared with the prestigious Bowral venue. The deciding factors really seem to have been the inclination of an Army Headquarters centred in Melbourne to have the facility near a capital city, in Victoria, and near an existing military base for ease of administration and use of existing training areas and ranges, with the land to be obtained without cost due to immediate budgetary difficulties. A site identified by Southern Command next to the Schools of Infantry and Tactics and Administration at Seymour with the nearby Puckapunyal training area promised to provide for this very adequately, though how the funds to build on the free land could be provided was not readily apparent.

Quarantine Building – Portsea 1953

The original ‘hospital’ was burnt down in 1916 and rebuilt to a much more generous standard than the remaining four. This would have meant a reasonable degree of comfort for the cadets had not the numbers required two to a room designed for one.

This, added to the lack of such a basic amenity as hot showers for young men undergoing a physically arduous course, made for more a difficult time than that being experienced at other army schools which, while in wartime buildings, at least had the benefit of adequate space, privacy, mains power and hot water.

December 1951 therefore saw the School committed to open at Portsea in the Quarantine Station as a very temporary expedient, with a site at Seymour agreed on provided some additional land could be acquired. But here once more the ministerial hand intervened, insisting that such further acquisition could be only with the consent of the landowner, who subsequently declined, as did the owner of an alternative block. Thus by the time of the graduation of the first class in mid-1952 there was not even the beginnings of a basis for a permanent site for the School, and to compound this no budgetary allocation for land acquisition or construction was available in 1952. This might either be regarded an ominous situation with the Health agreement expiring at the end of the year, or quite the contrary by the optimists who had noted that Cabinet had originally agreed that OCS could occupy the Portsea site provided that there was no immediate requirement for quarantine purposes, which of course the Department of Health plan did not envisage. DMT took heart from this, almost opportunistically, as it had been recognised from the start that such an establishment should have a prestigious site, and location at Seymour or the backstop of Watsonia hardly fitted that prescription. From minister downwards the Portsea area had rightly been described as magnificent, and these original feelings were hard to put aside for such mundane alternatives, so the elimination of inferior venues provided a welcome reason to firstly press for an extension of tenancy, then to manoeuvre for permanent occupancy of the quarantine area (3).

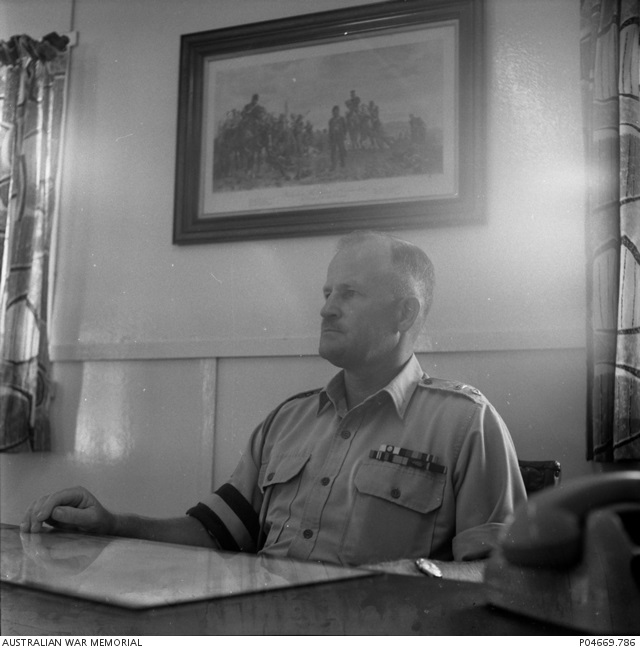

Major General Sir James William Harrison KCMG CB CBE 1912-1971

A graduate of the Royal Military College Duntroon in the depression era, he spent his earlier service in artillery appointments, and after attending the Middle East Staff School in 1941, filled a variety of staff appointments in AIF and Interim Army senior headquarters.

Harrison attended the UK Joint Services Staff College, then was an instructor at the Australian Staff College, followed by OCS as its founding Commandant.

His subsequent service included Quartermaster General and Adjutant General as a member of the Military Board, ending as General Officer Commanding Western Command. His final duty was as Governor of South Australia.

Nothing loathe to take advantage of this favourable turn, commandant Colonel J.W. Harrison submitted a report in July 1952 in which he pressed for taking over the Quarantine Station, or as an alternative building a new complex between the Leper Station and the Quarantine buildings, taking over the Quarantine reserve other than the small area containing the existing buildings. This area, when combined with the Defence Reserve, would also provide adequate space for ranges and close training areas. A last ditch attempt to adapt Watsonia camp was rejected on both the condition of buildings which would require complete reconstruction, plus the lack of range and training facilities, so the Minister was persuaded to return to the Minister for Health seeking the land other than the Station itself, with a further extension of a year of the current arrangement. And while the ministerial response was positive to both, the Director General of Health, who occupied the same professional standing in Health as does the present Chief of Defence Force within the Department of Defence, rejected the land transfer on the basis that it provided an isolation buffer for the station itself. Army responded agreeing to a limited buffer zone, but claiming the remainder of the reserve, which drew a positive response from Health, leading to agreement to alienation of the land but no positive action by Army to build. However, with the camel’s nose firmly in the tent, the existing occupancy arrangements were extended to the end of 1955, and in August 1954 a request was made for additional buildings and agreement to Army building activity to allow for the first extended one year course, which was scheduled to begin the following year (4).

Map 2 – Port Phillip and Environment

The Health Department was in something of a quandary. Cabinet had initially agreed to OCS occupancy of the site as long as the facilities were not required for active quarantine purposes, and the quarantine plan was for Fremantle and Sydney to be the active stations, with Portsea as no more than an emergency reserve, essentially for the remote prospect of international aircraft diverted from Sydney. This had obliged them to agree to conditional temporary occupancy, and this ongoing arrangement eroded their case for denying long term access, eventually leading to a de facto takeover. In a rearguard action, the Department of Health bureaucrats seized on an emergency use in April 1954 when the Strathaird arrived with smallpox on board, and although the School had successfully evacuated the area as agreed, an array of petty complaints was used to counter the Army request and demand that further facilities be built on that part of the reserve which had been transferred to Defence (5).

It was to be merely a delaying action. The School was well established, the Health case was tenuous, alternatives were now recognised to be both impractical and, with OCS’s enhanced status arising from the extended course and the career horizons which had promoted it, inappropriate for an academy which substantially matched that of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst: two years after long term tenure was granted in 1953 a belated restorative programme was commenced; and in the 1960s expansion additional accommodation blocks, an instructional complex and further administrative facilities were built without opposition from Health as the realpolitik of the day demanded (6). The Officer Cadet School had found its home.

Setting Up

The Military Board approved the formation of the Officer Cadet School ‘for the purpose of training selected categories of personnel for appointment as regimental officers in the ARA ‘. This was a simple enough aim, but when the wide disparity of backgrounds amongst entrants is considered, the difficulties of designing a short course are apparent: the initial entry comprised 23 ARA and 17 CMF non commissioned officers, many with broad military experience, 11 National Servicemen with three months basic training, and 21 civilians (7), some with a school cadet background. This problem of widely differing knowledge on entry to courses bedevils both military and civilian institutions attempting to carry out advanced training so that, where possible, entrance examinations are used to ensure a reasonable starting base, as happens with tertiary institutions and the Staff College. But OCS began with this great disparity which meant that basic military training had to be included in the syllabus to bring all candidates up to scratch, consuming time which might have been put to better use advancing knowledge at officer level. This was recognised but there was no time to engineer a solution for the first course, however from the second course onwards until the introduction of the one year course in 1955 which had the lattitude for introductory training, those entrants without adequate basic military skills were required to attend a three week pre-OCS course at the School of Infantry (8).

Colonel Ronald Selwyn Garland MC 1921-2002

A militia artillery officer in 1940, he transferred to the AIF, serving in commando and infantry units and 2 New Guinea Inf Bn during the war. He was awarded the Military Cross with 2/2 Indep Coy in 1944.

Postwar he was an instructor in 2 Rec Trg Bn, adjutant of 66 Inf Bn, and instructor at the School of Infantry for the RMC qualification courses conducted to qualify ex-AIF officers to enter the Australian Staff Corps under the Defence Act. His appointment in the rank of major as Senior Instructor for OCS in September 1951 followed naturally from there.

He subsequently filled training, staff and regimental appointments including Instructor Jungle Training Centre, CO Infantry Centre and CO 3 Trg Bn.

Captain David Allan Danson 1910-19xx

An Australian Instructional Corps officer in 1940, he then served in the AIF in infantry and engineer units. Postwar he returned to AIC then to RA Inf as instructor at the School of Infantry.

He was Quartermaster and Transport Officer at the School of Tactics and Administration when transferred to Quartermaster of OCS on 30 October 1951 to commence preparation for the opening of the School in January 1952.

Coming to a decision on the School’s initial location at Portsea Quarantine Station as late as 8 November, and detailed agreement with Department of Health on the facilities which would be made available on 30 November for a 7 January 1951 opening left little enough time for even the best of improvisers. Having a commandant and staff already appointed had of course allowed the preparation of stores and equipment requirements and development of training plans, together with assembly of personnel ready to move in. Site preparation was initiated by the despatch of an advance party under Capt D.A. Danson with Capt R. Wilson and 25 of the administrative staff to the Quarantine Station on 20 November to takeover accommodation, establish messing facilities and accumulate stores. Chief Instructor Maj R.S. Garland and the remaining members began moving in two weeks later, all being assembled by 16 December, while adjutant Capt M.B. McCrackan remained at Army Headquarters in Melbourne to facilitate the solving of last minute problems. Meanwhile commandant Harrison on 29 November began a selection board visit to all states to interview, assess and select the first course, a process which was to give short notice indeed to applicants who had to move to Portsea in the first week of the new year (9).

Captain Robert Wilson 1919-19xx

After service with the AIF in 2/15 Inf Bn he was assistant adjutant then intelligence officer of 66 Inf Bn in BCOF.

He was appointed Instructor OCS in the rank of captain in November 1951 to prepare for its opening in January 1952.

Breaking Ground

The OCS Campus

Apart from the impressive accommodation facilities of the Quarantine Station there was little on the site of the new academy to make it a satisfactory or even basic military training institution. For an educational establishment which was charged with training potential officers in basic military skills plus advanced subjects of tactics, administration and training techniques, there was an absence of not only firing ranges but also even indoor class rooms and outdoor training space. The open grassland of the early settlement had been taken over by ubiquitous ti-tree which covered the defence reserve completely. As classrooms for the 71 officer cadets the weatherboard emergency isolation buildings from 1919 provided an equally emergency refuge from the elements. Weapon training areas were burnt out of the scrub, reputedly by platoon commander Capt R. Wilson walking to suitable locations and dropping lighted matches in his trail. And as an extra-curricular activity the cadets spent Saturday mornings working on firing and grenade ranges and a confidence course. It was army make-do and can-do at its best: with only one year tenancy and the likelihood of relocation to another area, there would be no significant construction effort, so temporary facilities had to be developed, with a minimum of funded works programme and a maximum of self help.

Emergency Wards – Relics of 1919

In default of anything better, the old draughty, leaky huts provided some welcome shelter from the normal Victorian climate as a wet weather station for outdoor lessons, and for lecture rooms.

While the main buildings at the Quarantine Station had considerable potential given a reasonable quota of much overlooked maintenance and improvement, other facilities had to be improvised in a no-works funds environment.

This was not unusual in an army which was generally housed in temporary accommodation relics of the two world wars, so staff and students buckled down and made the most of what was available.

Nepean Historical Society

The other significant problem was living conditions. While the basic structures were sound, their upkeep had been kept at minimum care and maintenance levels as priorities for quarantine shifted elsewhere. As well the living accommodation which had been released to the School by the Department of Health was inadequate for the numbers involved, requiring two cadets to share a room which had been intended simply as the equivalent of a ship’s cabin. As for basic services, electric power came from two ageing 25 kva generators which were started at six in the morning to heat the water for showers which invariably ran out before all were done; it was switched off at what was literally lights out at 2200 hours, leaving cadets in the dark to catch up on any necessary study and equipment cleaning by torch light or hurricane lamp with blankets over the windows to avoid detection and retaliation (10).

Some augmentation of the efforts to make the area usable and habitable was found from two sources – the Citizen Military Forces engineers of 3rd Division held weekend bivouacs in the area, turning their training towards internal road improvement and scrub clearance in the training area, and there was some welcome provision of migrant labour. As assisted migrants were required to undertake two years directed employment at a Commonwealth establishment during the heavy inflow from the Continent in the 1950s it was fairly easy to get a complement of nineteen allotted to Portsea for a year to provide additional administrative staff and labour in preparation and improvement of roads, landscaping, sporting and training facilities (11). Not that this supplementary work force relieved the student body from aiding the groundwork, but it speeded the process and allowed diversion of works funds so saved to improving other training facilities.

Map 4 – OCS Area

By the end of 1952, with a further year tenancy agreed, an alternative permanent complex looked remote due to restrictions on the army works vote. The Commandant was moved to comment to Army Headquarters that he took it the School would remain at Portsea indefinitely. He saw little problem in an ongoing annual tenancy as far as outdoor training facilities were concerned, as these were developed and maintained by unit labour at negligible cost and located outside the quarantine area. He did however comment strongly on the lack of action to maintain the buildings in the station, citing long overdue painting, a collapse in the plumbing system which meant no hot water to the cadets living quarters and officers mess, and necessary repair of the windowless and leaky army huts used for classrooms. He further pointed out the need for an assembly hall-gymnasium for the future (12).

Road Building on the Campus – Portsea 1961

Self help was the trademark of Regular Army units which inherited the flimsy camps which had mushroomed in World War 2. It was usual that units used their members early mornings and Saturdays on self help programmes to make their facilities both habitable and workable.

OCS was no exception, with the cadets turned out to work on the sporting ovals and improving internal roads. Range practices had to be preceded by first building the ranges.

OCS Scrapbook 1961

By mid-July 1953 the classrooms had been made more habitable and mains power installed, landmarks in progress but also a commentary on the snail’s pace at which Department of Works responded to urgent requirements: a brake on progress in which it mirrored other departments which had a monopoly on activities which is only now being broken in the present decade, to the benefit of both national infrastructure and the public as a whole. It took a full year to provide an effective hot water service to the cadets, a penance which time-serving bureaucrats who felt no personal penalties in delays or failures neither appreciated nor cared about. As well there were many other areas where no progress at all had been made by the works service: in default of official funds and effort, unit labour was the only recourse to improve the ranges, tactical training areas, playing fields and landscaping. Cadets of later intakes had their long suffering predecessors to thank for much of the facilities and surroundings which they inherited (13).

With this much achieved there still remained the problem of tenure of the site. In the initial agreement of the School’s occupancy of the Portsea Quarantine Station was a clause requiring vacation within 24 hours in the event of a quarantine emergency. With Fremantle and Sydney designated the primary quarantine entry points for sea entry as the significant destinations and obvious clearing points in the 1950s and 60s, the potential for disruption was slight enough for an army desperate to find and then retain a site to which there was no effective alternative. Nevertheless the possibility of a quarantine occupation remained so it was necessary for cadets to pack all possessions in boxes prior to leaving Portsea for periods in excess of 24 hours so that they could be removed to an emergency site should this occur during their absence.

The switch of immigrants to air travel from the late 1960s and the increase of tourism by air increased the possibility of entry of individual cases of infectious disease, rather than the high volume contingencies which passenger ships brought, and this could be handled by using the Bungalow as an isolation area at Portsea rather than requiring the full facilities and consequent evacuation of OCS. This consequently eased the pressure and, in a less adversarial environment in which Department of Health had become accustomed to the OCS presence and the benefit of Army upkeep of the facilities, the practice of ‘boxing rooms’ was changed in 1968 to 72 hour absences (14). By 1978 it was finally accepted that the frequency and volume of international isolation cases did not warrant a separate Commonwealth facility, so responsibility was transferred to the State infectious diseases hospital at Fairfield, and the Quarantine Station finally closed.

Accompanying the 1953 decision to extend the tenancy at the Quarantine Station was a more formal approach to making both working and living accommodation progressively more habitable. A limited works programme, still tempered by shortages of funds and uncertain tenure, was directed at ameliorating the most urgent deficiencies. This was extended the following year to what amounted to almost luxuries: the extended course and overlapping class demanded use of the No 2 block which, with reduced course sizes, allowed cadets single use of rooms. That victory also encouraged further modest works expenditure which included repainting the whitewashed walls to pastel colours (15); the School was evolving from being a temporary creation in a widening variety of aspects.

Building an Academy

That the Army regarded the establishment of OCS as a landmark in solving its Regular officer needs is witnessed by the Chief of the General Staff Lt Gen S.F. Rowell giving the opening address on 7 January 1951, in effect the official opening of the institution. There then followed in succession Chairman of the Military Board Army Minister Francis and the remainder of the military members of the Board – Quartermaster General, Master General of the Ordnance, Deputy Chief of the General Staff and Adjutant General, a galaxy quite unknown at RMC, indicative of their support and perhaps curiosity. The same heavyweight team plus General Officer Commanding Southern Command Lt Gen H.C.F. Robertson also attended the first graduation in June 1952, so it was obvious to all that not only was the trip to Portsea from Melbourne both easy and pleasant but also that this School had the patronage of the full Army hierarchy (16).

Training problems were to a degree ameliorated for the second course onwards as the preliminary course at the School of Infantry enabled the basic training element in the course syllabus to be replaced by officer training for additional periods in staff duties, tactics and military history. The emphasis on instruction was also switched from lectures to syndicate discussions, the better to involve the students in the learning process and develop their capacity for reasoning and communication. From hereon for the succeeding five courses incremental refinements were made, accepting that 22 weeks was adequate to provide a basic grounding and assessment period which would be built on by post-graduate training and experience within units. On the first graduating class, the Commandant was able to report a generally satisfactory standard attained and ‘although some of those in the lower bracket have their limitations it is considered that they should all develop into satisfactory regimental officers’. And this latter was what the expectations were. For all that the Minister for Army had stated in his press release announcing the School in October 1951 that ‘there would be no appointments in the army for which an OCS graduate would not be eligible’, the aim was simply to fill the widening deficiency in junior officers. The first course was in fact told quite categorically by their mentors that their expectations were to rise no higher than the rank of major (18).

Towards Permanence

With the School having produced 196 graduates in its first two years on top of the other sources, the immediate crisis of the army officer shortage abated and thought was given to the content and extent of the course. The original objective of matching RMC’s training, less the academic content, required something more than a 22 week course, satisfactory though this had been given the more mature students admitted to Portsea to date. Experience arising from the teaching results of the initial courses had allowed a better balancing of time between subjects, particularly with the release of time through the pre-OCS Course coverage of basic drills and skills. But there remained an underlying misgiving that the graduates were not being given the depth of professional grounding which professional armies world wide recognised as appropriate. While short term commissions could be sustained by a short course specialising according to the nature of short term employment, a lifetime career, which was then the expectation by and of permanent officers, required adequate professional qualification, as Secretary Sinclair had warned at the beginning. The other factor was that intakes of younger students and soldiers with less experience required a maturation period which only a minimum of a year of, as second commandant Col T.F. Cape put it, ‘moulding’ would meet. The course was doubled to one year in 1955, the January entrants graduating in December, with a mid-year overlapping junior class (19).

Third Pre-OCS Course – School of Infantry, Seymour, July 1953

The course provided preparation for those selected for entry for the fourth course at OCS but with no substantial basic military skills. While the three week period was considerably shorter than the 12 week recruit course for regular soldiers at Kapooka, through the concentrated attentions of a captain and four warrant officers, the 36 candidates were brought to reasonable standards so they were not either well behind their more experienced classmates, or a drag on the content and pace of the OCS course. Entrants to later long courses had no such relief.

The pain of the accelerated training at Seymour was more than offset by that saved in an otherwise desperate early struggle for survival at Portsea.

OCS Scrapbook 1953

The new approach manifested itself in outward symbols: while the first classes had been designated as for normal army instructional courses, eg No 6 Course, they now became intakes, reflecting recognition as a permanent military academy, although the School title was retained. A sword of honour supplemented the Governor General’s Medal as presentations to outstanding graduates, and the title of the senior cadet changed from the normal army rank of WO2 to that of CSM. There remained however a degree of ambivalence on the future of the School. While pressure had been maintained on Department of Health through 1954 to cede the majority of the Health reserve and more buildings for accommodation for extended courses, Army Headquarters was also debating the continuing need for OCS. The original Military Board decision had allowed that the near-1,000 deficiency in Regular officers should be overcome gradually over five years to ensure that the right material could be found, and that thereafter the courses could be reduced to cover replacements. Finally the DCGS could provide firm justification for the need for an annual output of 100 a year up to the end of 1957 only, but also came to the conclusion that extension to and beyond 1960 was justified at the rate of 70 per year, with any surpluses in Regular officers so generated to be offset by reducing the numbers of RASR and short service commissioned officers (20).

This was confirmed in the Wade Committee Report of 1958 which recommended that OCS should be retained indefinitely for training officer cadets for permanent commissions to the extent of about 20 percent of the annual requirement, the remainder being accommodated by RMC, Officer Qualifying Courses at the School of Tactics and Administration, Quartermaster Commissions and direct entry for some tertiary qualified specialists. This was approved by the Military Board, not only cementing OCS as an ongoing institution but also underlining the need for permanent facilities rather than the makeshift ones which served for classrooms, library, hall and gymnasium. But with a fall off in the demand for graduates, proposed by Wade at 40 per year, and indeed the number of applicants and entrants in the later 1950s, there was little incentive for the Army to commit scarce building funds to permanent facilities on a site where occupancy was still permissive. It was not until the expansion arising from the 1963 national service scheme and the subsequent commitment to Vietnam that a serious attempt was made to establish the infrastructure on a permanent and enlarged basis (21).

Such a short notice increase in officer requirements underlined one of the purposes for which OCS was established – to provide a shorter lead time conduit for officer production. The Military Board consequently determined in 1964 that OCS should produce 140 Australian graduates a year, the same as RMC’s increased target, so reversing the 1958 decision. With that specific target a specific impetus was given to providing the wherewithal to meet it: a third cadet accommodation block plus an assembly hall and library were built in that year, then a fourth accommodation building and gymnasium in 1965, accompanied by extensive tree planting and landscaping which enhanced the campus’ original natural beauty. This flowed on in the next four years to new officers and sergeants messes, 10-bed medical centre, squash court, two new ovals to make a total of seven, two extra tennis courts to make four, plus a new Quartermaster complex, training staff offices, and extra living facilities for the administrative staff (22). An indoor heated swimming pool was needed to round off the complex, but this was overtaken by a halt to permanent development at the beginning of the 1970s.

Thus, in the second decade of its existence the Officer Cadet School established itself as the major officer producing academy of the Australian Army. It operated on the traditional spartan lines of high pressure, high discipline, restricted privileges and directed activities which were held to be the right mix of environment in producing officers able to face the rigours of military life and provide the example and leadership for which they were destined as regimental officers. And with the expansion of horizons which accompanied acceptance that the Portsea officer would in fact be an equal part of the ongoing mainstream officer corps rather than a solution to a short term shortage, the School had expanded then refined its programme to meet the educational needs of long-career regular officers and was graduating a product acknowledged to be eminently satisfactory.

Graduation Presentations – OCS 16 December 1954

Chief of the General Staff Lt Gen Sir Ragnar Garrett CB CBE presented diplomas and prizes to the graduates. The Military Board ensured that senior officers continued overt support for the School at its more important occasions.

With the most spartan of facilities still the norm, the presentation had to take place in obviously cramped quarters. Recipient of his graduation certificate is E.J. Charlton.

Photo: E.J. Charlton

References

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 DMT 1982 of 27 September 1950, 10 April 1951, 5 August 1951; Ministerial Telephone Minute of 5 July 19951; Secretary Army Minute of 26 July 1951; QMG Minute of 9 August 1951.

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 Proceedings of a Conference on the Proposed Use of the Quarantine Buildings at Portsea; Minister for Health letter of 8 November 1951.

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 DQMG 706 Of 15 October 1952; DMT 1356 of 6 October 1952.

- AA MP927 A259/18/319 of 14 November 1951, 10 January 1952; A259/18/29 OCS 8/16/1 of 31 July 1952; Department of Health 874/10/1 of 8 April 1953; A259/18/183(Q2) of 23 April 1952, 3 August 1954.

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 Minister for Health letter of 30 September 1954; cf OCS 8/16/534 of 7 October 1954.

- AA MP927 A259/18/183 of 31 March, 8 April 1953, 3 August 1954.

- MP897/1 AHQ 24495 of 20 December 1951.

- 82453/1 R7231111 Pt A OCS Report 17 December 1952, p4. 9. Welch Portsea,

- Welch Portsea, p13-4; AA MP 897/1 27/32/3 of 9 November 1951.

- AA 8245311 R723/1/1 OCS Report 12 June 1952, p8-9; Interviews I.G. Hands, P.F. Kent, R.G .Lange, I. Throssell.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report 12 June 1952, p9; 17 December 1952, p7.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report 17 December 1952, p6-7.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report July 1953, p6.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 7/1/3 of 10 July 1968.

- AA 82453/1 R7231111 OCS Report December 1955, p4, 8-9.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report 12 June 1952, p4.

- AA 82453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report 12 June 1952, p9.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report 17 December 1952, p4-5; 12 June 1952, p6; July 1953, p5; 9 December 1953, p4; 28 June 1954, p3; December 1954, p3; Interviews R.G. Lange et al.

- RMC Archives Miscellaneous OCS Commandants’ Graduation Addresses 1955.

- AA MP 927/1 A259/181319 DCGS Minute 1038 of 9 August 1954.

- AWM MSS 1479 AHQ 182/R2/12 of31 July 1967 DPA Paper, p2.

- AWM MSS 1479 A1821R2?12 of 31 July 1967; AA B2453/1 R72311/1 OCS Reports 1963-67.